From the series of classic literature vs the future…

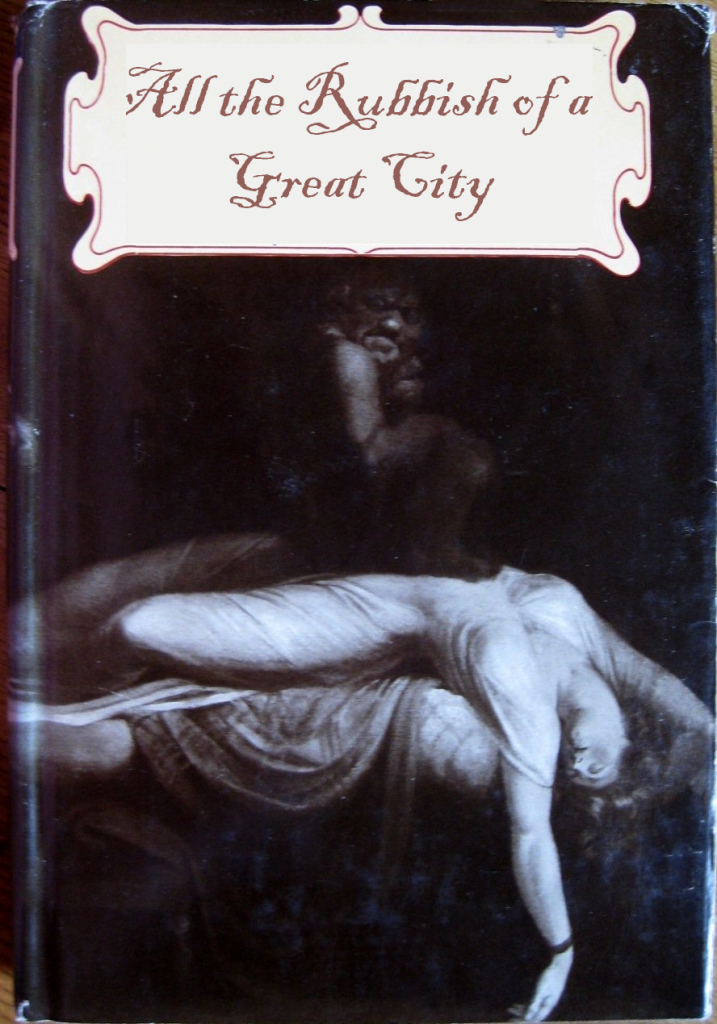

All The Rubbish of a Great City

Part 1: No Sun Ever Since That Day

Dear Farewell

You may be glad to see your letter of 6th April last from me. You are still in the good humour of the last time, and I believe that the people will be kind and kind to you in your letters.

I hope you will send me the following on the 15th of June: 1st: to my brother, a messenger, and my wife; 2nd: my daughter; and to my sister; then my brother; and my sister to my husband; and my brother to my son; and my father to my son; and my daughter to my husband and sons; and to my daughter’s father.

It is impossible for me to perceive a trace of the abominable scenes which I have experienced. There are but a few houses destroyed, and most of them, that is, very pretty ones, and all are occupied with families, and a few shops: one street is covered with all the rubbish of a great city; its streets are of a grey nature; and the streets are all closed off by some heavy iron gate.

I take a seat in a corner of the square; and after taking food from a little table and taking a seat beside a shopkeeper, or at least an old man with a hat on, I look about me. Nothing remarkable is seen or seen; there is no ruin or any signs of destruction; you might as well go near the ruins of the pyramids. The women seem to be quite contented, and are making the little fires that are burning. We are very anxious, we are very sad, to see them.

As I was about to arrive at the coast, I was suddenly knocked out by the wind; my companions, who were not surprised, rushed to me. I lay in their arms, and told them I could not recover myself, and said it was time for my expedition to proceed.

I begged them to give me some of the best part of the sea to make my recovery. They assented, and then threw out with me a large quantity of salt that I could not bring home to myself, and I fell dead.

They gave me some of their gold as I lay dying.

I never heard of such an occurrence; I should have been ashamed to have done so; but I had too much hope in the fortune of the sea; for if I were lost by such misfortunes, one does not have what has been given him; for if the fortune be bad, man do have a right to hope.

They put me into the boat with their captain, Sir Richard, and took me back to the ship where we were sitting. I lay there several days; I thought I had done well, but they told me the fortune was the same; the sun set over the mountains that night, and gave no sun ever since that day.

My mind was so troubled about my condition, that I could not bear the noise of the ship, so I cried, and fell into a terrible state of sleep, and then lay, my head, and neck, and legs, down upon a bed.

[These words, which do not make any impression on the ear, should appear to prove the correctness of the saying.]

Original

Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus

Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin) Shelley 1818

Letter 1

To Mrs. Saville, England.

St. Petersburgh, Dec. 11th, 17—.

You will rejoice to hear that no disaster has accompanied the commencement of an enterprise which you have regarded with such evil forebodings. I arrived here yesterday, and my first task is to assure my dear sister of my welfare and increasing confidence in the success of my undertaking.

I am already far north of London, and as I walk in the streets of Petersburgh, I feel a cold northern breeze play upon my cheeks, which braces my nerves and fills me with delight. Do you understand this feeling? This breeze, which has travelled from the regions towards which I am advancing, gives me a foretaste of those icy climes. Inspirited by this wind of promise, my daydreams become more fervent and vivid. I try in vain to be persuaded that the pole is the seat of frost and desolation; it ever presents itself to my imagination as the region of beauty and delight.

There, Margaret, the sun is for ever visible, its broad disk just skirting the horizon and diffusing a perpetual splendour. There—for with your leave, my sister, I will put some trust in preceding navigators—there snow and frost are banished; and, sailing over a calm sea, we may be wafted to a land surpassing in wonders and in beauty every region hitherto discovered on the habitable globe. Its productions and features may be without example, as the phenomena of the heavenly bodies undoubtedly are in those undiscovered solitudes. What may not be expected in a country of eternal light?

I may there discover the wondrous power which attracts the needle and may regulate a thousand celestial observations that require only this voyage to render their seeming eccentricities consistent for ever. I shall satiate my ardent curiosity with the sight of a part of the world never before visited, and may tread a land never before imprinted by the foot of man.

These are my enticements, and they are sufficient to conquer all fear of danger or death and to induce me to commence this laborious voyage with the joy a child feels when he embarks in a little boat, with his holiday mates, on an expedition of discovery up his native river. But supposing all these conjectures to be false, you cannot contest the inestimable benefit which I shall confer on all mankind, to the last generation, by discovering a passage near the pole to those countries, to reach which at present so many months are requisite; or by ascertaining the secret of the magnet, which, if at all possible, can only be effected by an undertaking such as mine.

…Etc…

Your affectionate brother,

R. Walton